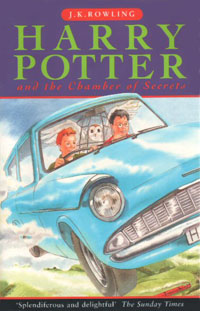

Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets

| Harry Potter books Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Author | J. K. Rowling |

| Illustrators | Cliff Wright (UK) Mary GrandPré (US) |

| Genre | Fantasy |

| Publishers | Bloomsbury (UK) Arthur A. Levine/ Scholastic (US) Raincoast (Canada) |

| Released | 2 July 1998 (UK) 2 June 1999 (US) |

| Book no. | Two |

| Sales | Unknown |

| Story timeline | 13 June 1943 31 July 1992- 29 May 1993 |

| Chapters | 18 |

| Pages | 251 (UK) 341 (US) |

| ISBN | 0747538492 |

| Preceded by | Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone |

| Followed by | Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban |

Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets is the second novel in the Harry Potter series written by J. K. Rowling. The plot follows Harry's second year at Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry, during which a series of messages on the walls on the school's corridors warn that the "Chamber of Secrets" has been opened and that the "heir of Slytherin" will kill all pupils who do not come from all-magical families. These threats are followed by attacks which leave residents of the school "petrified" (that is, frozen). Throughout the year, Harry and his friends Ron Weasley and Hermione Granger investigate the attacks, and Harry is confronted by Lord Voldemort, who is attempting to regain full power.

The book was published in the United Kingdom on 2 July 1998 by Bloomsbury and in the United States on 2 June 1999 by Scholastic Inc. Although Rowling found it difficult to finish the book, it won high praise and awards from critics, young readers and the book industry, although some critics thought the story was perhaps too frightening for younger children. Some religious authorities have condemned its use of magical themes, while others have praised its emphasis on self-sacrifice and on the way in which a person's character is the result of the person's choices.

Several commentators have noted that personal identity is a strong theme in the book, and that it addresses issues of racism through the treatment of non-magical, non-human and non-living characters. Some commentators regard the diary as a warning against uncritical acceptance of information from sources whose motives and reliability cannot be checked. Institutional authority is portrayed as self-serving and incompetent.

The film version of Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets, released in 2002, became the third film to exceed $600 million in international box office sales and received generally favourable reviews. However, The Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers won the Saturn Award for the Best Fantasy Film. Video games loosely based on Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets were also released for several platforms, and most obtained favourable reviews.

Contents |

Synopsis

Plot introduction

In the first novel in the series, the main character, Harry Potter, has struggled with the difficulties of growing up and the added challenge of being a famous wizard. When Harry was a baby, Voldemort, the most powerful Dark wizard in history, killed Harry's parents but mysteriously vanished after trying to kill Harry. This results in Harry's immediate fame and his being placed in the care of his Muggle, or non-magical, Aunt Petunia and Uncle Vernon.

Harry enters the wizarding world at the age of eleven and is enrolled in Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry. He makes friends with Ron Weasley and Hermione Granger and is confronted by Lord Voldemort trying to regain power.

Plot summary

Soon after the start of Harry's second year at Hogwarts, messages on the walls of the corridors say that the mythical Chamber of Secrets has been re-opened and that the "heir of Slytherin" will kill all pupils whose parents are both Muggles. Over the next few months, various inhabitants of the school are found petrified in corridors. Meanwhile, Harry, Ron, and Hermione discover Moaning Myrtle, the ghost of a girl who was killed the last time the Chamber was opened and now haunts the girls' toilet in which she died. Myrtle shows Harry a diary bearing the name Tom Marvolo Riddle. Although its pages are blank, it responds when Harry writes in it. Eventually the book shows him Hogwarts as it was fifty years ago. There he sees Tom Riddle, Head Boy at the time, blame Rubeus Hagrid, who was then thirteen years old and already kept dangerous creatures as pets, for opening the Chamber.

Four months later the diary is stolen, and shortly afterward Hermione is petrified. However, she holds a note explaining that the culprit is a basilisk, a huge serpent whose gaze kills those who look into its eyes directly but only petrifies those who see their reflection. Hermione concluded that the monster travels through the school's pipes and emerges through the toilet Myrtle haunts. As the attacks continue, Cornelius Fudge, the Minister for Magic, holds Hagrid in the wizards' prison as a precaution. Lucius Malfoy, Draco's father and a former supporter of Voldemort who claims to have reformed, announces that the school's governors have suspended Dumbledore from the position of headmaster.

After Ron's younger sister, Ginny, is taken into the Chamber, the staff insist that the Defese Against the Dark Arts teacher, Gilderoy Lockhart, should handle the situation. However, when Harry and Ron go to his office to tell him what they have discovered about the basilisk, Lockhart reveals that he is a fraud who took credit for the accomplishments of others and attempts to erase the boys' memories. Disarming Lockhart, they march him to Moaning Myrtle's toilet, where Harry opens the passage to the Chamber of Secrets. In the sewers under the school, Lockhart grabs Ron's wand and tries again to wipe the boys' memories, but since Ron's wand had been damaged, the spell backfires, inflicting total amnesia on Lockhart, collapsing part of the tunnel, and separating Harry from Ron and Lockhart.

While Ron attempts to tunnel through the rubble, Harry enters the Chamber of Secrets, where Ginny lies beside the diary. As he examines her, Tom Riddle appears, looking exactly as he did fifty years ago, and explains that he is a memory stored in the diary. Ginny wrote in it about her adolescent hopes and fears, and Riddle won her confidence by appearing sympathetic, possessed her, and used her to open the Chamber. Riddle also reveals that he is Voldemort as a boy. He further explains that he learned from Ginny who Harry was and about his own deeds as Voldemort. When Ginny realised that she had been responsible for the attacks, she attempted to throw the diary away, which is how it came into Harry's possession. Riddle then releases the basilisk to kill Harry. Dumbledore's pet phoenix, Fawkes, brings a magnificent sword wrapped in the Sorting Hat. Harry uses the sword to kill the basilisk, but only after being bitten by the creature's venomous fangs, one of which breaks off. As Riddle gloats over the dying Harry, Fawkes cries on Harry's wound to cure it. Harry stabs the diary with the broken fang, and Riddle vanishes.[1] Ginny revives and they return to Ron, who is still watching over the amnesic Lockhart. Fawkes carries all four out of the tunnels.

Harry recounts the whole story to Dumbledore, who has been reinstated. When Harry mentions his fears that he is similar to Tom Riddle, Dumbledore says that Harry chose Gryffindor House, and only a true member of that House could have used Godric Gryffindor's sword to kill the basilisk. Lucius Malfoy bursts in, and Harry accuses him of slipping the diary into one of Ginny's books while the pupils were shopping for school books. Finally, the basilisk's petrified victims are revived by a potion, the preparation of which has taken several months.

Publication and reception

Development

Rowling found it difficult to finish Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets because she was afraid it would not live up to the expectations raised by Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone. After delivering the manuscript to Bloomsbury on schedule, she took it back for six weeks of revision.[2]

In early drafts of the book, the ghost Nearly Headless Nick sang a self-composed song explaining his condition and the circumstances of his death. This was cut as the book's editor did not care for the poem, which has been subsequently published as an extra on J. K. Rowling's official website.[3] The family background of Dean Thomas was removed because Rowling and her publishers considered it an "unnecessary digression", and she considered Neville Longbottom's own journey of discovery "more important to the central plot".[4]

Publication

Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets was published in the UK on 2 July 1998 and in the US on 2 June 1999.[5][6] It immediately took first place in UK bestseller lists, displacing popular authors such as John Grisham, Tom Clancy,[2] and Terry Pratchett,[7] and making Rowling the first author to win the British Book Awards Children's Book of the Year for two years in succession.[8] In June 1999 it went straight to the top of three US bestseller lists,[9] including The New York Times'.[10]

First edition printings had several errors, which were fixed in subsequent reprints.[11] Initially Dumbledore said that Voldemort was the last remaining ancestor of Salazar Slytherin, instead of his descendant.[11] Gilderoy Lockhart's book on werewolves is entitled Weekends with Werewolves at one point and Wanderings with Werewolves later in the book.[12]

Critical response

"Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets" was met with near universal acclaim. In The Times, Deborah Loudon described Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets as a children's book that would be "re-read into adulthood" and highlighted its "strong plots, engaging characters, excellent jokes and a moral message which flows naturally from the story".[13] Fantasy author Charles de Lint agreed, and considered the second Harry Potter book as good as Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone, a rare achievement among series of books.[14] Thomas Wagner regarded the plot as very similar to that of the first book, based on searching for a secret hidden under the school. However, he enjoyed the parody of celebrities and their fans that centres round Gilderoy Lockhart, and approved of the book's handling of racism.[15] Tammy Nezol found the book more disturbing than its predecessor, particularly in the rash behaviour of Harry and his friends after Harry withholds information from Dumbledore, and in the human-like behaviour of the mandrakes used to make a potion that cures petrification. Nevertheless she considered the second story as enjoyable as the first.[16]

Mary Stuart thought the final conflict with Tom Riddle in the Chamber was almost as scary as in some of Stephen King's works, and perhaps too strong for young or timid children. She commented that "there are enough surprises and imaginative details thrown in as would normally fill five lesser books." Like other reviewers, she thought the book would give pleasure to both children and adult readers.[17] According to Philip Nel, the early reviews gave unalloyed praise while the later ones included some criticisms, although they still agreed that the book was outstanding.[18]

Writing after all seven books had been published, Graeme Davis regarded Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets as the weakest of the series, and agreed that the plot structure is much the same as in Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone. He described Fawkes's appearance to arm Harry and then to heal him as a deus ex machina: the book does not explain how Fawkes knew where to find Harry; and Fawkes's timing had to be very precise, as arriving earlier would probably have prevented the battle with the basilisk, while arriving later would have been fatal to Harry and Ginny.[19]

Dave Kopel describes the climactic scene in which Harry saves Ginny from Riddle's diary and the basilisk as Pilgrim's Progress for a new audience: "Harry descends to a deep underworld, is confronted by two Satanic minions (Voldemort and a giant serpent), is saved from certain death by his faith in Dumbledore (the bearded God the Father/Ancient of Days), rescues the virgin (Ginerva [sic] Weasley), and ascends in triumph."[20]

Awards and honours

Rowling's Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets was the recipient of several awards.[21] The American Library Association listed the novel among its 2000 Notable Children's Books,[22] as well as its Best Books for Young Adults.[23] In 1999, Booklist named Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets as one of its Editors' Choices,[24] and as one of its Top Ten Fantasy Novels for Youth.[21] The Cooperative Children's Book center made the novel a CCBC Choice of 2000 in the "Fiction for Children" category.[25] The novel also won Children's Book of the Year British Book Award,[26] and was shortlisted for the 1998 Guardian Children's Award and the 1998 Carnegie Award.[21]

Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets won the Nestlé Smarties Book Prize 1998 Gold Medal in the 9–11 years division.[26] Rowling also won two other Nestlé Smarties Book Prizes for Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone and Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban. The Scottish Arts Council awarded their first ever Children’s Book Award to the novel in 1999,[27] and it was also awarded Whitaker's Platinum Book Award in 2001.[21][28]

Religious response

Religious controversy surrounding Harry Potter and the Chamber of the Secrets and the other books in the Harry Potter series mainly deal with claims that the novel contains occult or Satanic subtexts. Religious response to the series has not been exclusively negative, however, and several religious groups have spoken in defense of the moralistic themes found in the book. The American Library Association even placed the series atop the "most challenged books" list for 1999–2001.[29]

The Orthodox churches of Greece and Bulgaria have campaigned against the series,[30][31] and in the United States, calls for the book to be banned from schools have led to legal challenges. Most of these are held on the grounds that witchcraft is a government-recognised religion and that to allow the novels to be held in public schools violates the separation of church and state.[32][33][34]

Some religious responses have been positive. Emily Griesinger wrote that fantasy literature helps children to survive reality for long enough to learn how to deal with it, described Harry's first passage through to Platform 9¾ as an application of faith and hope, and his encounter with the Sorting Hat as the first of many in which Harry is shaped by the choices he makes. She noted that the self-sacrifice of Harry's mother, which protected the boy in the first book and throughout the series, was the most powerful of the "deeper magics" that transcend the magical "technology" of the wizards, and one which the power-hungry Voldemort fails to understand.[35] Christianity Today published an editorial in favour of the books in January 2000, calling the series a "Book of Virtues" and averring that although "modern witchcraft is indeed an ensnaring, seductive false religion that we must protect our children from", the Harry Potter books represent "wonderful examples of compassion, loyalty, courage, friendship, and even self-sacrifice".[36] "At least as much as they've been attacked from a theological point of view", commented Rowling, "[the books] have been lauded and taken into pulpit, and most interesting and satisfying for me, it's been by several different faiths".[37]

Themes

Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets continues the examination of what makes a person who he or she is, which began in the first book. As well as maintaining that Harry's identity is shaped by his decisions rather than any aspect of his birth,[16][38]Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets provides contrasting characters who try to conceal their true personalities: as Tammy Nezol puts it, Gilderoy Lockhart "lacks any real identity" because he is nothing more than a charming liar.[16] Riddle also complicates Harry's struggle to understand himself by pointing out the similarities between the two: "both half-bloods, orphans raised by Muggles, probably the only two Parselmouths to come to Hogwarts since the great Slytherin."[39]

Opposition to class, prejudice, and racism is a constant theme of the series. In Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets Harry's consideration and respect for others extends to the lowly, non-human Dobby and the ghost Nearly Headless Nick.[29] According to Marguerite Krause, achievements in the novel depend more on ingenuity and hard work than on natural talents.[40]

Edward Duffy, an associate professor at Marquette University, says that one of the central characters of Chamber of Secrets is a book, Tom Riddle's enchanted diary, which takes control of Ginny Weasley – just as Riddle planned. Duffy suggests that Rowling intended this as a warning against passively consuming information from sources that have their own agendas.[41] Although Bronwyn Williams and Amy Zenger regard the diary as more like an instant messaging or chat room system, they agree about the dangers of relying too much on the written word, which can camouflage the author, and they highlight a comical example, Lockhart's self-promoting books.[42]

Immorality and the portrayal of authority as negative are significant themes in the novel. Marguerite Krause states that there are few absolute moral rules in Harry Potter's world, for example Harry prefers to tell the truth, but lies whenever he considers it necessary – very like his enemy Draco Malfoy.[40] At the end of Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets, Dumbledore retracts his promise to punish Harry, Ron, and Hermione if they break any more school rules – after Professor McGonagall estimates that they have broken over 100 – and lavishly rewards them for ending the threat from the Chamber of Secrets.[43] Krause further states that authority figures and political institutions receive little respect from Rowling.[40] William MacNeil of Griffith University, Queensland, Australia states that the Minister for Magic is presented as a mediocrity.[44] In his article "Harry Potter And The Secular City", Ken Jacobson suggests that the Ministry as a whole is portrayed as a tangle of bureaucratic empires, saying that "Ministry officials busy themselves with minutiae (e.g. standardising cauldron thicknesses) and coin politically correct euphemisms like 'non-magical community' (for Muggles) and 'memory modification' (for magical brainwashing)."[38]

This novel implies that it begins in 1992: the cake for Nearly-Headless Nick's 500th deathday party bears the words "Sir Nicholas De Mimsy Porpington died 31 October 1492".[45][46]

Connection to Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince

Chamber of Secrets has many links with the sixth book of the series, Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince. In fact, Half-Blood Prince was the working title of Chamber of Secrets and Rowling says she originally intended to present some "crucial pieces of information" in the second book, but ultimately felt that "this information's proper home was book six".[47] Some objects that play significant roles in Half-Blood Prince first appear in Chamber of Secrets: the Hand of Glory and the opal necklace that are on sale in Borgin and Burkes; a Vanishing Cabinet in Hogwarts that is damaged by Peeves the Poltergeist; and Tom Riddle's diary, which is later shown to be a Horcrux.[48]

Adaptations

Film

The film version of Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets was released in 2002.[49] Chris Columbus directed the film,[50] and the screenplay was written by Steve Kloves. It became the third film to exceed $600 million in international box office sales, preceded by Titanic, released in 1997, and Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone, released in 2001.[51] The film was nominated for a Saturn Award for the Best Fantasy Film,[51] but The Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers took the prize.[52] According to Metacritic, the film version of Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets received "generally favourable reviews" with an average score of 63%,[53] and another aggregator, Rotten Tomatoes, gave it a score of 82%.[50]

Video game

Video games loosely based on the book were released in 2002, mostly published by Electronic Arts but produced by different developers:

| Publisher | Year | Platform | Type | Metacritic score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electronic Arts | 2002 | MS Windows | Role-playing game[54] | 77%[55] |

| Aspyr | 2002 | Mac | Role-playing game[54] | (not available) |

| Electronic Arts | 2002 | Game Boy Color | Role-playing game[56] | (not available) |

| Electronic Arts | 2002 | Game Boy Advance | Adventure/puzzle game[57] | 76%[58] |

| Electronic Arts | 2002 | GameCube | Action adventure[59] | 77%[60] |

| Electronic Arts | 2002 | PlayStation | Role-playing game[61] |

|

| Electronic Arts | 2002 | PlayStation 2 | Action adventure[63] | 71%[60] |

| Electronic Arts | 2002 | Xbox | Action adventure[64] | 77%[65] |

See also

References

- ↑ This is the sequence in the book; see Rowling, J.K. (1998). Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets. London: Bloomsbury. pp. 236–237. ISBN 0747538484.. In the film, Harry stabs the diary before being healed by Fawkes; see Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets. Warner Brothers. 2002. http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0295297/. Retrieved 25 May 2009.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Sexton, Colleen (2007). "Pottermania". J. K. Rowling. Twenty-First Century Books. pp. 77–78. ISBN 0822579499. http://books.google.com/?id=J_IPN8UMf7IC&pg=PA77&dq=%22Harry+Potter+and+the+Chamber+of+Secrets%22. Retrieved 25 May 2009.

- ↑ Rowling, J.K. (2009). "Nearly Headless Nick". http://www.jkrowling.com/textonly/en/extrastuff_view.cfm?id=11. Retrieved 25 May 2009.

- ↑ Rowling, J.K. (2009). "Dean Thomas's background (Chamber of Secrets)". http://www.jkrowling.com/textonly/en/extrastuff_view.cfm?id=2. Retrieved 25 May 2009.

- ↑ "A Potter timeline for muggles". Toronto Star. 14 July 2007. http://www.thestar.com/entertainment/article/235354. Retrieved 27 September 2008.

- ↑ "Harry Potter: Meet J.K. Rowling". Scholastic Inc. 1999-2006. http://www.scholastic.com/harrypotter/books/author/index.htm. Retrieved 27 September 2008.

- ↑ "Digested read: Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets". The Guardian (London). 25 August 1998. http://www.guardian.co.uk/books/1998/aug/25/booksforchildrenandteenagers. Retrieved 25 May 2009.

- ↑ Beckett, Sandra (2008). "Child-to-Adult Crossover Fiction". Crossover Fiction. Taylor & Francis. pp. 112–115. ISBN 041598033X. http://books.google.com/?id=9ipnQ2ryU7IC&pg=PA114&lpg=PA114&dq=%22Harry+Potter+and+the+Philosopher%27s+Stone%22+book+sales+bestseller. Retrieved 16 May 2009.

- ↑ Pais, Arthur (20 June 2003). "Harry Potter: The mania continues...". Rediff.com India Limited. http://www.rediff.com/news/2003/jun/20spec1.htm. Retrieved 25 May 2009.

- ↑ "Best Sellers Plus". The New York Times. 20 June 1999. http://www.nytimes.com/books/99/06/20/bsp/fictioncompare.html. Retrieved 25 May 2009.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Brians, Paul. "Errors: Ancestor / Descendant". Washington State University. http://www.wsu.edu/~brians/errors/ancestor.html. Retrieved 25 May 2009.

- ↑ Rowling, J.K. (1998). Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets. London: Bloomsbury. pp. 38, 78. ISBN 0747538484.

- ↑ Loudon, Deborah (18 September 1998). "Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets — Children's Books". The Times (London). http://entertainment.timesonline.co.uk/tol/arts_and_entertainment/books/children/article778375.ece. Retrieved 26 May 2009.

- ↑ de Lint, Charles (January 2000). Books To Look For. Fantasy & Science Fiction. http://www.sfsite.com/fsf/2000/cdl0001.htm. Retrieved 26 May 2009.

- ↑ Wagner, Thomas (2000). "Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets". Thomas M. Wagner. http://www.sfreviews.net/harrypotter2.html. Retrieved 26 May 2009.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 Nezol, Tammy. "Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets (Harry Potter 2)". About.com. http://contemporarylit.about.com/od/fantasy/fr/harryPotter2.htm. Retrieved 26 May 2009.

- ↑ Stuart, Mary. "Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets". curledup.com. http://www.curledup.com/chamber.htm. Retrieved 26 May 2009.

- ↑ Nel, Phillip (2001). "Reviews of the Novels". J.K. Rowling's Harry Potter novels: a reader's guide. Continuum International. pp. 55. ISBN 0826452329. http://books.google.com/?id=qQYfoV62d30C&pg=PA54&dq=%22Harry+Potter+and+the+Chamber+of+Secrets%22. Retrieved 26 May 2009.

- ↑ Davis, Graeme (2008). "Re-reading Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets". Re-Read Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets Today! an Unauthorized Guide. Nimble Books LLC. p. 1. ISBN 1934840726. http://books.google.com/?id=mrvPPS5DXBEC&pg=PA2&dq=%22Harry+Potter+and+the+Chamber+of+Secrets%22. Retrieved 25 May 2009.

- ↑ Dave Kopel (2003). "Deconstructing Rowling". National Review. http://www.nationalreview.com/kopel/kopel062003.asp. Retrieved 23 June 2007.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 "Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets". Arthur A. Levine Books. 2001 - 2005. http://www.arthuralevinebooks.com/book.asp?bookid=28. Retrieved 18 July 2009.

- ↑ "ALA Notable Children's Books All Ages 2000". Scholastic Inc.. 11/6/07. http://bookwizard.scholastic.com/tbw/viewBooklist.do?dp=%3D%3FUTF-8%3FB%3FYm9va2xpc3RJZD05OTg5OTcmc2hhcmVkPXRydWU%3D%3F%3D. Retrieved 18 July 2009.

- ↑ "Best Books for Young Adults". American Library Association. 2000. http://www.ala.org/ala/mgrps/divs/yalsa/booklistsawards/bestbooksya/2000bestbooks.cfm. Retrieved 18 July 2009.

- ↑ Estes, Sally; Susan Dove Lempke (1999). "Books for Youth - Fiction". Booklist. http://www.booklistonline.com/default.aspx?page=show_product&pid=3603404. Retrieved 18 July 2009.

- ↑ "Harry Potter Reviews". CCBC. 2009. http://www.education.wisc.edu/ccbc/books/hpreviews.asp. Retrieved 18 July 2009.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 "ABOUT J.K. ROWLING". Raincoast Books. 2009. http://www.raincoast.com/harrypotter/rowling.html. Retrieved 18 July 2009.

- ↑ "Scottish Arts Council Children's Book Awards". Scottish Arts Council. 30 May 2001. http://www.scottisharts.org.uk/1/latestnews/1001908.aspx. Retrieved 18 July 2009.

- ↑ "Potter goes platinum". RTÉ. 2009. http://www.rte.ie/arts/2001/0921/harrypotter.html. Retrieved 18 July 2009.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Knapp, Nancy (2003). "In Defense of Harry Potter: An Apologia". School Libraries Worldwide (International Association of School Librarianship) 9 (1): 78–91. http://www.iasl-online.org/files/jan03-knapp.pdf. Retrieved 14 May 2009.

- ↑ Clive Leviev-Sawyer (2004). "Bulgarian church warns against the spell of Harry Potter". Ecumenica News International. http://www.eni.ch/articles/display.shtml?04-0394. Retrieved 15 June 2007.

- ↑ "Church: Harry Potter film a font of evil". Kathimerini. 2003. http://www.ekathimerini.com/4dcgi/_w_articles_politics_100021_14/01/2003_25190. Retrieved 15 June 2007.

- ↑ Ben Smith (2007). "Next installment of mom vs. Potter set for Gwinnett court". Atlanta Journal-Constitution. http://web.archive.org/web/20070601155533/http://www.ajc.com/metro/content/metro/gwinnett/stories/2007/05/28/0529metPOTTER.html. Retrieved 8 June 2007.

- ↑ "Georgia mom seeks Harry Potter ban". Associated Press. 4 October 2006. http://msnbc.msn.com/id/15127464/.

- ↑ Laura Mallory (2007). "Harry Potter Appeal Update". HisVoiceToday.org. http://www.hisvoicetoday.org/hpappeal.htm. Retrieved 16 May 2007.

- ↑ Griesinger, Emily (2002). "Harry Potter and the "deeper magic": narrating hope in children's literature". Christianity and Literature 51 (3): 455–480. http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_hb049/is_3_51/ai_n28919307/. Retrieved 15 May 2009.

- ↑ Editorial (10 January 2000). "Why We Like Harry Potter". Christianity Today.

- ↑ Gibbs, Nancy (19 December 2007). "Time Person of the Year Runner Up: JK Rowling". Time inc.. http://www.time.com/time/specials/2007/personoftheyear/article/0,28804,1690753_1695388_1695436,00.html. Retrieved 23 December 2007.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 Jacobsen, Ken (2004). "Harry Potter And The Secular City: The Dialectical Religious Vision Of J.K. Rowling". Animus 9: 79–104. http://www2.swgc.mun.ca/animus/Articles/Volume%209/jacobsen.pdf. Retrieved 27 May 2009.

- ↑ Cockrell, Amanda (2004). "Harry Potter and the Secret Password". In Whited, L.. The ivory tower and Harry Potter. University of Missouri Press. pp. 20–26. ISBN 0826215491. http://books.google.com/?id=iO5pApw2JycC&pg=PA15&dq=%22Harry+Potter+and+the+Chamber+of+Secrets%22. Retrieved 27 May 2009.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 40.2 Krause, Marguerite (2006). "Harry Potter and the End of Religion". In Lackey, M., and Wilson, L.. Mapping the world of Harry Potter. BenBella Books. pp. 55–63. ISBN 1932100598. http://books.google.com/?id=sKRkzVIK3foC&pg=PT12&dq=%22Harry+Potter+and+the+Chamber+of+Secrets%22. Retrieved 27 May 2009.

- ↑ Duffy, Edward (2002). "Sentences in Harry Potter, Students in Future Writing Classes". Rhetoric Review, (Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.) 21 (2): 170–187. doi:10.1207/S15327981RR2102_03. http://wrt-brooke.syr.edu/courses/205.03/rrhp.pdf. Retrieved 27 May 2009.

- ↑ Williams, Bronwyn; Zenger, Amy (2007) (in WilliamsZenger2007Literacy). Popular culture and representations of literacy. A.A.. Routledge. pp. 113–117, 119–121. ISBN 0415360951. http://books.google.com/?id=DDvbNnO4OH8C&pg=PA119&lpg=PA119&dq=%22chamber+of+secrets%22+riddle+identity. Retrieved 27 May 2009.

- ↑ Rowling, J.K. (1998). "Dobby's Reward". Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets. London: Bloomsbury. pp. 241–243. ISBN 0747538484.

- ↑ MacNeil, William (2002). ""Kidlit" as "Law-And-Lit": Harry Potter and the Scales of Justice". Law and Literature (University of California) 14 (3): 545–564. doi:10.1525/lal.2002.14.3.545. http://www98.griffith.edu.au/dspace/bitstream/10072/6871/1/21489.pdf. Retrieved 27 May 2009.

- ↑ Rowling, J.K. (1998). Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets. London: Bloomsbury. p. 102. ISBN 0747538484.

- ↑ Whited, L. (2006). "1492, 1942, 1992: The Theme of Race in the Harry Potter Series". The Looking Glass : New Perspectives on Children's Literature 1 (1). http://www.lib.latrobe.edu.au/ojs/index.php/tlg/article/view/97/82. Retrieved 20 August 2009.

- ↑ Rowling, J.K. (29 June 2004). "Title of Book Six: The Truth". http://www.jkrowling.com/textonly/en/news_view.cfm?id=77. Retrieved 25 May 2009.

- ↑ Davis, Graeme (2008). "Re-reading The Very Secret Diary". Re-Read Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets Today! an Unauthorized Guide. Nimble Books LLC. p. 74. ISBN 1934840726. http://books.google.com/?id=mrvPPS5DXBEC&pg=PA74&dq=%22Chamber+of+Secrets%22+%22Half-Blood+Prince%22+horcrux. Retrieved 25 May 2009.

- ↑ Schwarzbaum, Lisa (13 November 2002). "Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets (2002)". Entertainment Weekly. http://www.ew.com/ew/article/0,,389817~1~0~harrypotterandchamber,00.html. Retrieved 8 August 2009.

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 "Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets (2002) - Rotten Tomatoes". IGN Entertainment, Inc. http://uk.rottentomatoes.com/m/harry_potter_and_the_chamber_of_secrets/. Retrieved 26 May 2009.

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 "SF Site - News: 25 March 2003". http://www.sfsite.com/columns/news0303.htm. Retrieved 26 May 2009.

- ↑ "Past Saturn Awards". Academy of Science Fiction, Fantasy & Horror Films. 2006. http://www.saturnawards.org/past.html#fantasy. Retrieved 26 May 2009.

- ↑ "Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets (2002): Reviews". Metacritic. http://www.metacritic.com/video/titles/harrypotterandthechamberofsecrets?q=Harry%20Potter%20and%20the%20Chamber%20of%20Secrets. Retrieved 26 May 2009.

- ↑ 54.0 54.1 "Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets (PC)". IGN Entertainment, Inc.. 1996-2009. http://uk.pc.ign.com/objects/487/487290.html. Retrieved 18 July 2009.

- ↑ "Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets (PC)". CBS Interactive Inc.. 2009. http://www.metacritic.com/games/platforms/pc/harrypotterchamber?q=Harry%20Potter%20and%20the%20Chamber%20of%20Secrets. Retrieved 18 July 2009.

- ↑ "Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets". IGN Entertainment, Inc.. 1996-2009. http://uk.gameboy.ign.com/objects/487/487326.html. Retrieved 18 July 2009.

- ↑ "Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets". IGN Entertainment, Inc.. 1996-2009. http://uk.gameboy.ign.com/objects/482/482092.html. Retrieved 18 July 2009.

- ↑ "Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets". CBS Interactive Inc.. 2009. http://www.metacritic.com/games/platforms/gba/harrypotterchamber?q=Harry%20Potter%20and%20the%20Chamber%20of%20Secrets. Retrieved 18 July 2009.

- ↑ "Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets". IGN Entertainment, Inc.. 1996-2009. http://uk.cube.ign.com/objects/017/017306.html. Retrieved 18 July 2009.

- ↑ 60.0 60.1 "Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets (Cube)". CBS Interactive Inc.. 2009. http://www.metacritic.com/games/platforms/cube/harrypotterchamber?q=Harry%20Potter%20and%20the%20Chamber%20of%20Secrets. Retrieved 18 July 2009.

- ↑ "Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets". IGN Entertainment, Inc.. 1996-2009. http://uk.psx.ign.com/objects/491/491764.html. Retrieved 18 July 2009.

- ↑ "Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets (PSX)". CBS Interactive Inc.. 2009. http://www.metacritic.com/games/platforms/psx/harrypotterchamber?q=Harry%20Potter%20and%20the%20Chamber%20of%20Secrets. Retrieved 18 July 2009.

- ↑ "Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets". IGN Entertainment, Inc.. 2009. http://uk.ps2.ign.com/objects/482/482688.html. Retrieved 18 July 2009.

- ↑ "Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets". IGN Entertainment, Inc.. 1996-2009. http://uk.xbox.ign.com/objects/482/482248.html. Retrieved 26 May 2009.

- ↑ "Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets (XBX)". CBS Interactive Inc.. 2009. http://www.metacritic.com/games/platforms/xbx/harrypotterchamber?q=Harry%20Potter%20and%20the%20Chamber%20of%20Secrets. Retrieved 26 May 2009.

External links

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||